Welcome to Ceramic Review

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

Ceramic Review Issue 326

March/April 2024

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

March/April 2024

Neil Brownsword, winner of the Whitegold Prize Quartz Award has created new artworks currently on display in two locations in St Austell. Dr Katie Bunnell, curator of the Prize, explains more

The Whitegold International Ceramics Prize, launched in 2019, is designed to bring St Austell’s wealth of history and global connections through china clay to the attention of ceramic artists across the world. It invites artists to submit works that use clay to inspire new perspectives and insights into place – the specific character of a location that makes it unique. A shortlist of ten artists, whittled down by the Whitegold Prize jury from over 100 submissions, visited St Austell for an introduction to the town and its surrounding clay pits and tips and to present their work at the Whitegold Festival in 2019. This introduction to St Austell’s clay country contributed to proposals for new artworks that would create connections between people, culture and place.

SKILLS AND PROCESSES

Professor Neil Brownsword was selected for the first prize Quartz Award and between lockdowns in 2020, he created interventions in St Austell at White River Place, the town’s shopping centre, and at Wheal Martyn Clay Works, the UK’s china clay mining museum. In these works he reconnects the histories of St Austell and the Potteries of North Staffordshire, bound by legacies of industrial scale mining and the transformation of china clay. As a Professor of Ceramics at North Staffordshire University, Brownsword is a researcher interested in human labour, craft skill and the processes involved in ceramic production. Through revealing hidden actions, processes and the performance of raw materials in a combination of film and object installations, he highlights overlooked forms of human ingenuity embedded within objects, places and practices connected through the material culture of clay.

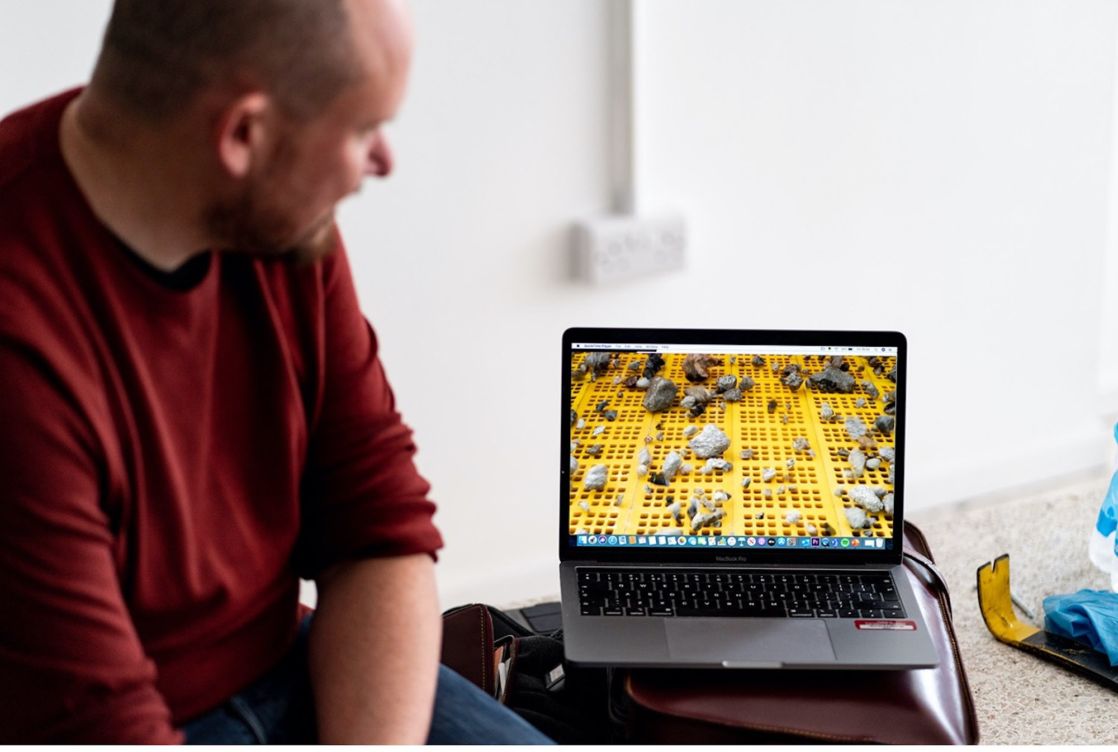

Brownsword notes that: ‘The principles of china clay or ‘kaolin’ extraction and refining have changed little since 1746. The arduous labour once performed by teams of workers with picks and shovels has been substituted by bulldozers, centrifugal gravel pumps, jaw crushers and belt conveyors. With the advances of automated technology, bodily engagements with this landscape are now reduced largely to sedentary contact with vehicles, keyboards and tele-remote systems that control and transform clay country’s industrial topography. These ‘performative landscapes’ coined as ‘taskscapes’ by the social anthropologist Tim Ingold, remain an active assemblage of human and material actions that intertwine in a constant state of flux.’ Called Taskscape, Brownsword’s intervention at White River Place involves a combination of film, text and a display of clay refining tools. Inspired by the processes he encountered on a tour of Imerys’ china clay refining plants as part of the Whitegold fieldtrip, he was granted permission to return to the refining plants to gather film footage. ‘I was entranced by the visuality of the processes, the transformation of materials from liquid to solid. I wanted to make something poetic with just these visuals,’ Brownsword explains.

Taskscape is an artwork that offers up industrial phenomena for poetic contemplation, processes that bring into being a material we frequently encounter, but perhaps don’t notice in our daily existence, from the medicines we consume, to the tableware from which we eat and drink. Brownsword adds: ‘For the people who work in the industry, they never really give any of it a second thought – it’s just work. So I wanted to reframe the everyday as something worth a second glance.’

EXPLORING HERITAGE

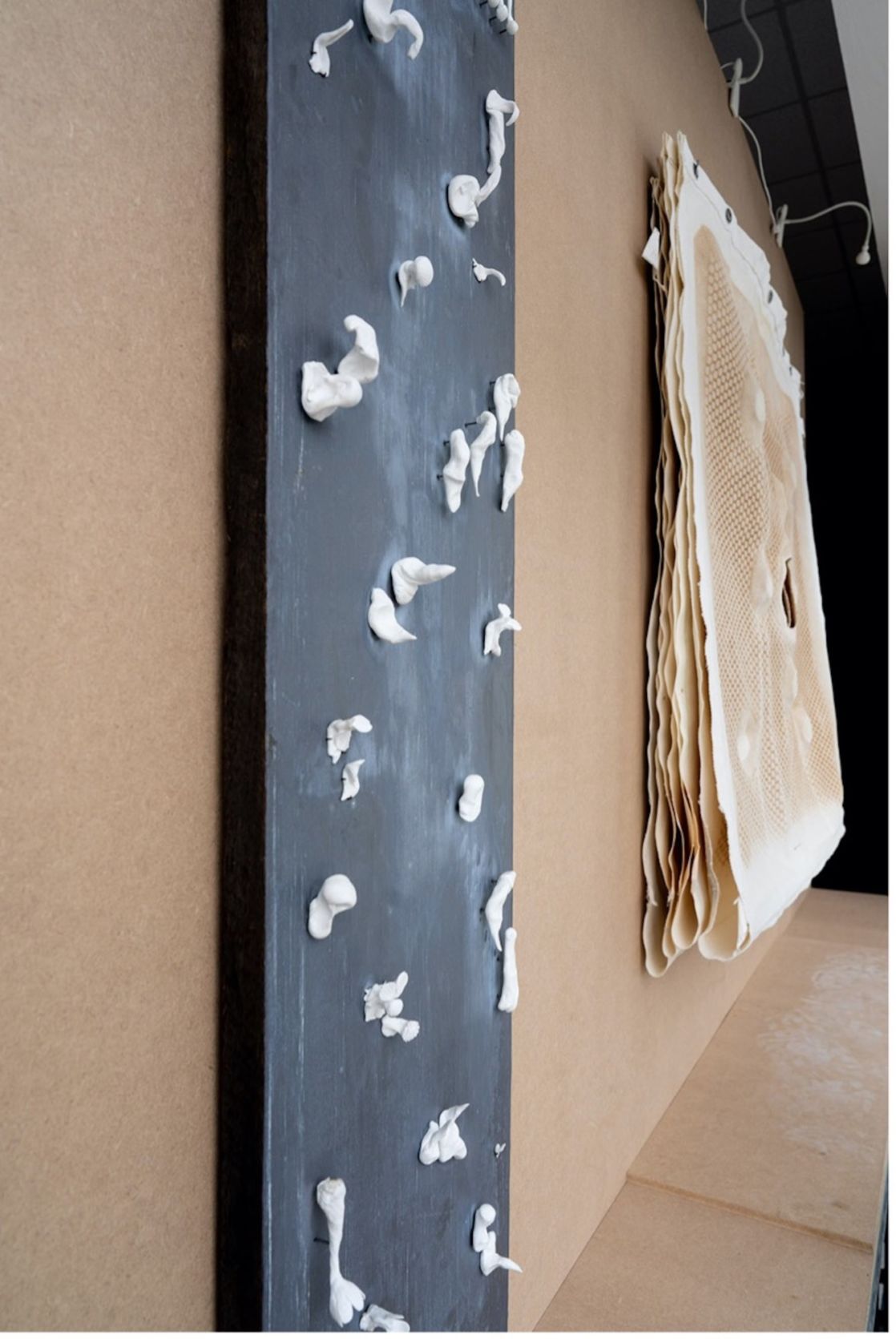

At Wheal Martyn Clay Works, Brownsword has recreated Relic, a new iteration of his project of more than five years with Stoke-on-Trent flower maker Rita Floyd. Wheal Martyn’s curator Jo Moore welcomes Brownsword’s intervention concurring with his view that: ‘A lot of people see heritage as something static. I’m fascinated by exploring heritage through working with communities, sharing stories and memories. Heritage is about the present and the future.’ The Clay Works museum has a direct view into a working pit as well as preserved workings, including a large clay pan kiln where wet china clay would have been shovelled onto hot ceramic tiles to dry out. ‘The spaces at Wheal Martyn are loaded with memory, history and traces of work,’ Brownsword says. ‘The moment I stepped into the pan kiln it had a presence that I wanted to activate in a different way.’ Relic is a re-evaluation of the endangered craft of china flower making.

Through the deconstruction of the intuitive hand movements that Floyd uses, Brownsword evidences the subtleties of touch involved in the process. Hundreds of small, seemingly insignificant pieces of bone china clay are carefully arranged across the greying, clay tiles of the pan kiln floor, where up until the late 1960’s, raw china clay would have been piled for drying out.

Some shapes are recognisably flower like, some piled up into pyramids are reminiscent of the sky tips created from the overspill from the china clay extraction that are a feature of St Austell’s landscape, all are records of a highly practiced hand gesture. Moore believes Brownsword’s piece serves to strengthen links between St Austell and Stoke-on-Trent and that it will attract new audiences as well as shedding new light on the pan kiln for regulars: ‘What Neil has installed is extraordinary, in particular the visual contrast between the industrial backdrop of the pan kiln floor and the white luminosity of the bone china fragments.’ Brownsword will be returning to St Austell in June 2021 for a residency at Wheal Martyn as part of the Whitegold Festival where Floyd will join him to do flower making demos. Ever the ambitious optimist, he says: ‘I am hoping to work together with workshop participants, to find ways of shaping three tonnes of raw china clay with Victorian hand tools designed for tableware production.’ Brownsword’s work for the Whitegold Prize will also form part of his exhibition, Alchemy and Metamorphosis at The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stoke-onTrent that will coincide with the British Ceramic Biennial later this year.

The Whitegold International Ceramics Prize is curated by Dr Katie Bunnell for Whitegold, the Austell Project ceramic strand; www.austellproject.co.uk Brownsword’s work for Whitegold Prize 2019 has been made possible with the support of Coastal Communities, Arts Council England, Spode Museum Trust and North Staffordshire University