Welcome to Ceramic Review

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

Ceramic Review Issue 326

March/April 2024

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

March/April 2024

Ten female ceramists whose work has changed perception of modern studio ceramics are the focus of a new exhibition at Oxford Ceramics Gallery. Could this show, asks Sue Herdman, spur more in the same vein?

There have always been pioneering women in ceramics. Émigré Lucie Rie, arriving in London in 1938, tutored in the ideals of the Modern Movement, turned clay into art form. Dora Billington, starting at the Central School of Art in 1919, became a progressive force in ceramics education. On it goes, a roll call of women who have pushed boundaries, explored and experimented with form and challenged our notions of ceramics. Many current ceramists have an international profile, creating work that defies classification and draws collectors. Yet exhibitions that focus on such female makers are not common.

But times are changing. In the wider art world awareness of the underrepresentation of women artists is rising. Each March – Women’s History Month – the hashtag #5WomenArtists spurs global digital discussion, asking: ‘can you name five women artists?’. Last year some 1,800 cultural organisations in 57 countries went online to answer the challenge. And there’s a stirring in sales houses. Jenny Saville’s self-portrait Propped became the most expensive work by a living female artist, selling in 2018 for £9.5m. Current women artists have soaring solo shows: reference Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at Tate last year, and the Paula Rego exhibition to come. Yet, still, a recent survey by Artnet and the podcast ‘In Other Words’ revealed that only 11% of all works gathered by top USA museums were by women. ‘It’s the idea of women artists being more of a risk, which seems to speak to a sort of institutional timidity,’ ‘In Other Words’ told The New York Times.

GENERATIONAL INFLUENCES

Perhaps it is no surprise then that it is a small, independent gallery, the type that can be fleet of foot – and possibly more audacious – that is prepared to take a ‘risk’ and stage a ceramics exhibition dedicated to female artists. Pioneering Women at the Oxford Ceramics Gallery features 40 works by ten female ceramists across three generations, whose work spans the 1950s to the present day. ‘The history of ceramics is at the heart of what we do,’ say James Fordham and Rachel Ackland of the gallery, ‘and we are aware that much of that history is dominated by men. But we are interested in women makers. Those featured in this show have changed the trajectory of ceramics; their work has huge influence.’ The ten are Lucie Rie, Ladi Kwali, Bodil Manz and Magdalene Odundo; Akiko Hirai, Jennifer Lee, Deirdre McLoughlin and Alison Britton; Carol McNicoll and Inger Rokkjaer.

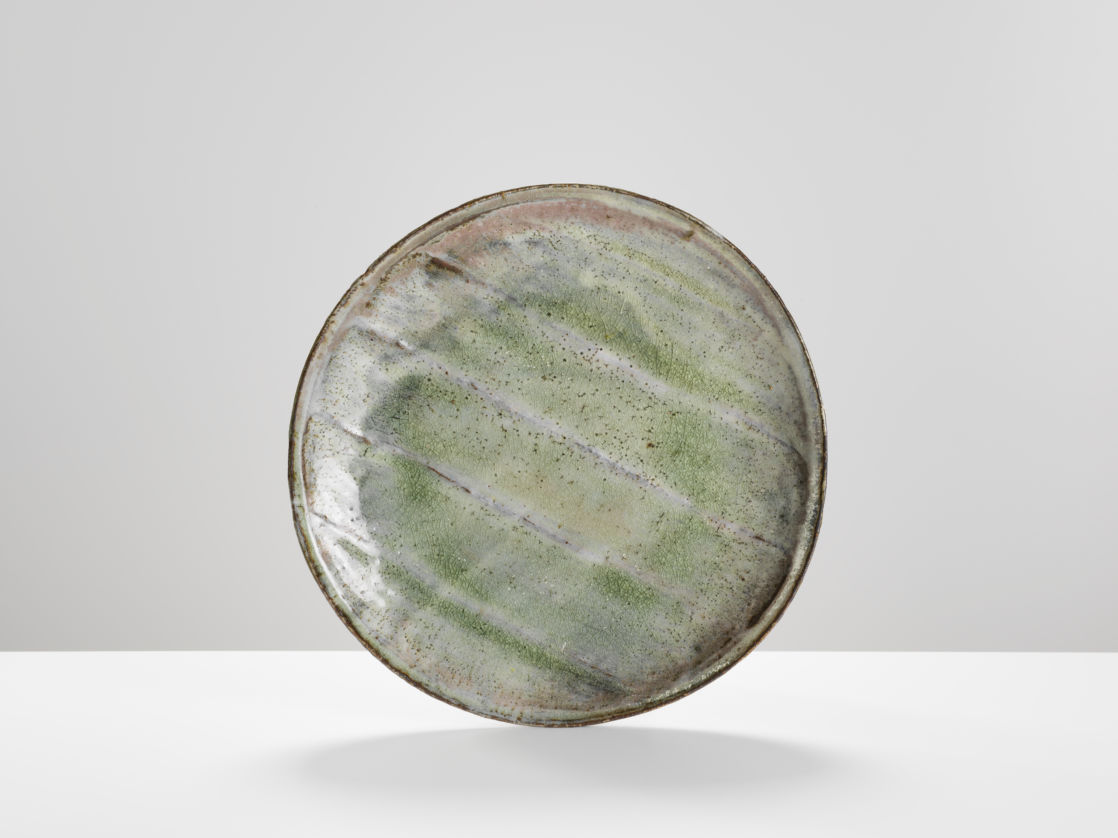

Work by Akiko Hirai; Image by Michael Harvey

Lucie Rie; courtesy of Oxford Ceramics Gallery

This show has come with challenges for curator Amanda Game, not least that Covid-19 meant studio visits were out, replaced by Zoom. ‘The gallery space is also not large,’ she adds, ‘so discipline was needed in our choices.’ The results are a genuine exploration of very different, groundbreaking styles. The juxtaposing of pieces that have not been shown together before (and in McLoughlin’s case, rarely in the UK) create a fresh dynamic, with additional surprises (a drawing from Odundo; a textile from McNicoll). There are Rokkjaer’s fiery yellow, raku-fired stoneware pieces, with their subtle mix of Danish clay and Asian technique and, from Manz, silky porcelain groupings. From Jennifer Lee come signature, pure, smooth, still pieces, a contrast to the explosive, rugged forms from Hirai, the youngest in the show. For function and form there is the mottled green-glazed and incised surface of Kwali’s earthy, beautiful 1960s Water Jar. And there is the purely sculptural: sensuous, sophisticated, tactile diamond polished works by McLoughlin.

Almost all the works, bar McLoughlin’s, are vessels. This wasn’t entirely intentional, says Game – that correlation between woman and vessel form was not being consciously made. ‘We were just looking for interesting work, from Hirai’s continued capacity to surprise, to the finely balanced humour of McNicoll’s making.’

Viewing the works – with their connections to other places – opens avenues of thinking, not least on how movement across the globe, so confined in recent times, can be key in realising pioneering work. ‘It leads to that amalgamation of differing traditions in such exciting ways,’ Game comments, pointing to Kwali’s encounter with Michael Cardew in Africa, and the subsequent Japanese and English elements then woven into her work (including, on one pot, a London red bus). Another avenue, of course, is gender bias. ‘I wouldn’t say that any of these ceramists has felt constrained by being a woman,’ says Game, ‘but curating this has led me to think more about countries such as Japan. Fewer female than male potters follow that well-trodden path from Japan to the UK. It is harder to find Japanese female artists working there. That is something I would like to explore more.’

Work by Akiko Hirai; Image by Michael Harvey

RADICAL APPROACHES

Another strand is just how swiftly these makers were picked up and why this was so. ‘At the moment they appeared, they were doing something different,’ says Game. ‘Each has taken their medium away from pots,’ add Fordham and Ackland, ‘crossing into the art world, breaking barriers.’ McNicoll and Britton were, of course, part of that extraordinary generation, graduating from

the Royal College of Art in the early 1970s – ‘The London Ladies’ whose radical approach to ceramics deconstructed the notion of the functional in playful but powerful ways. Here, Britton’s 2015 Outridge, bringing vessel to sculpture again, is evidence of her ongoing exploration in that area. Early Vessel, from Odundo, reveals the thrum of presence that was already there in her starting-out years. Odundo’s practice is example, too, of how early interest in such work has remained steadfast. The subject of recent, hugely successful shows at the Sainsbury Centre and The Hepworth Wakefield, her Angled Mixed Coloured vessel fetched a world record at auction for a single work by

a living ceramic artist last year, going for £240,000.

Magdalene Odundo; courtesy of Oxford Ceramics Gallery

Lucie Rie; courtesy of Oxford Ceramics Gallery

It is interesting to hear that these artists expressed surprise at being shown together. The mix is certainly unusual. But there is something that firmly binds these women and their approach to ceramics: a phenomenal commitment to their work and a very personal expression within their medium. ‘They have never felt the need to ask permission or conform to a particular expectation,’ explains Game. ‘None of them have ever wavered, or stopped exploring.’

She describes this exhibition as ‘a modest entry into a field that has potential for greater exploration, one that could inspire larger arts institutions to examine their stored collections for work by women potters.’ There’s no doubt such investigations would provide a new way of looking at collections, of asking questions, and, yes, of staging more shows that investigate the remarkable strides women artists have made in clay.

Pioneering Women, Oxford Ceramics Gallery,

until 27 March; oxfordceramics.com

Subscribe to read more articles like this inside the March/April 2021 issue of Ceramic Review.